Prefer audio? Listen to Bishop Steven’s podcast on Spotify.

Long ago the prophet Ezekiel was given a commission by God to be a watchman or a sentinel. The watchman’s job was to give a clear warning of threats or danger. This was a serious task – a matter of life or death for the city and for the nation. Ezekiel’s call comes twice in the book which bears his name (in 3.16-21 and 33.1-9).

Over the summer I put my name to an open letter to Sir Demis Hassabis, the Founder and Chief Executive of Google DeepMind. I’m one of sixty UK Parliamentarians to sign up to the letter, which was put together by Pause AI and was published on 29 August.

The launch of the letter was covered by TIME magazine last week. The article carries comments from my colleagues in the House of Lords, Baroness Kidron and Lord Browne, former Secretary of State for Defence, and from myself.

The letter is from a coalition of voices who together want to be sentinels: sounding a warning to the whole of our society and the whole world of an unseen danger in the rapid development and roll out of immensely powerful generative AI tools.

The letter targets Google DeepMind because the company signed up to the Frontier AI Safety Commitments in February 2024, following an international AI summit co-hosted by the UK and South Korea. One of those commitments was that companies should safety test their products before release and publish full details of those tests.

But in March 2025, Google released Gemini 2.5 Pro - but failed to release the detailed information testing for over a month. If companies fail to keep to international agreements on AI safety, the world is sleepwalking into madness and danger.

My own background in AI

I’ve been engaging with the benefits and risks of Artificial Intelligence through my work in the House of Lords for around a decade now. I was part of the original Lords Select Committee enquiry into AI in 2017-18, which published an authoritative overview of the whole field.

I was then one of the founding Board Members of the UK Government’s Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation from 2019 and am still a member of an informal cross party group of peers who worked together to develop, improve and monitor the Online Safety Act.

Bishop Steven spoke in the House of Lords this week, asking questions about the impact of AI on the UK youth unemployment rate.

Benefits and risks

I’m absolutely clear that AI has the potential to bring great benefits to humankind in the fields of medicine and the sciences, as well as daily life. But I’m also very clear that there are huge risks in the present, not simply the distant future. Those risks cut deep into areas of individual and societal well being. They risk eroding key parts of what it means to be human and key parts of a flourishing society.

For the last decade there has been a growing gap between the deployment of this technology in many different and sensitive areas of national life and public debate and building understanding about what is happening.

We need a much wider and deeper conversation.

When the UK government hosted the first global AI summit in 2024, the key output from the summit was a rather strange conversation between then Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, and the tech titan Elon Musk on AI potential and safety. It’s good to have a dialogue between senior levels of government and the tech companies, but where is the place at the table for the citizens and consumers?

Concern among young people

As the Diocese of Oxford, we hosted around 100 young people from Church secondary schools across the diocese to our clergy conference this year to listen to their concerns. Each of them had prepared a short statement about their top level anxieties about the world.

Top of the list? Technology, AI, mobile phone use, the power of the technology companies.

That snapshot is backed up by all of the research. The rise of social media and excessive availability of powerful smartphones to adolescents has contributed to a mental health pandemic among the young.

The new generative AI tools are now adding to the risk in all kinds of ways. Very often the discussion about AI risk is being framed in terms of future existential risk. As and when general artificial intelligence is developed and released then there are huge questions for the very existence of our species. These risks need to be taken seriously. A new book is to be published this month under the title: If anyone builds it, everyone dies (by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares, Vintage, 2025).

But sometimes the projection of risk and alarm into the future obscures the present danger. The careless release of immensely powerful tools by global companies now, without transparent safety testing, is harming individuals and society directly and indirectly.

Summer reading

Earlier in the summer, I expanded on these themes on the AI Adoption podcast with Professor Ashley Braganza of Brunel University.

Over the summer months I’ve been engaging more directly with the risks of generative AI – the kind of tools which Google DeepMind and other companies are now incorporating into everyday search engines and software, and in particular with Chatbots.

Parmy Olson has charted the story of the development of Google DeepMind and Open AI through the careers of the two founders, Demis Hassabis and Sam Altman. Her book Supremacy was the FT’s Business Book of the Year in 2024.

Parmy weaves a gripping narrative of accelerating development and of an AI race to bring products to market in order to generate a vast potential return on the investment needed in computer power to train and deliver AI. It is this global arms race between the major tech companies which leads to greater and further recklessness in open release and an aversion to external scrutiny.

Olson takes great pains to point out that the founders of DeepMind came into the field with a mission to develop AI in an ethical way – which makes Google’s recent practice even more disturbing.

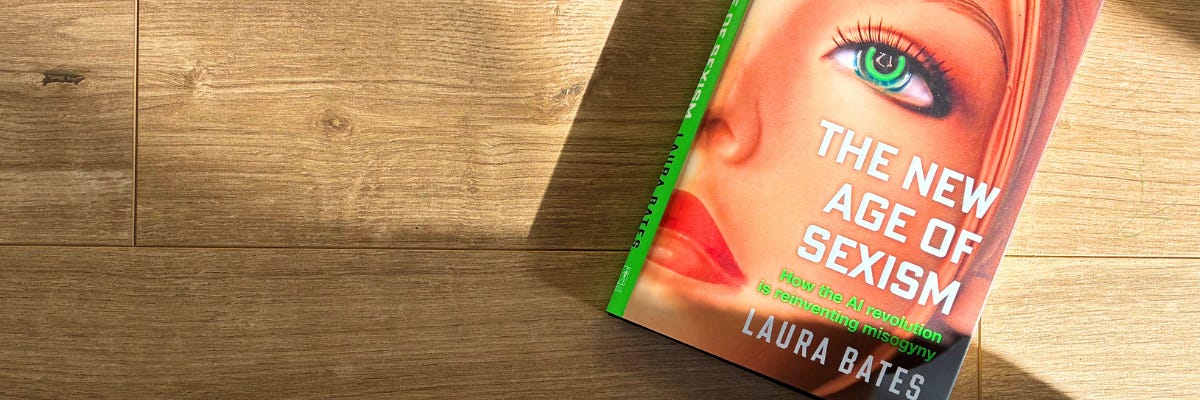

Laura Bates’ new book is not for the faint hearted: The New Age of Sexism: How the AI Revolution is Reinventing Misogyny (Simon and Schuster, 2005). Bates chronicles the more disturbing developments in AI and robotics, many of which, she argues, harm and disadvantage women.

Her chapters cover deepfakes and in particular the production and distribution of shaming images; sexual harassment in virtual environments; sex robots and cyber brothels; image-based sexual abuse; and AI girlfriends and boyfriends.

I was left in little doubt that these intended and unintended uses of AI tools are distorting one of the most fundamental aspects of being human: our deepest relationships and our sexuality.

A distorting of humanity

Olson and Bates are sentinels: drawing society’s attention to serious risks to try to prevent our sleepwalking into madness.

The Times reported just this week that the NHS has now issued a warning to the public that chatbots should not be used for therapy because “they deliver harmful and dangerous mental health advice”. But that is exactly how the latest chatbots are being used, especially by the young.

You can see how its happening. According to one poll last year, more than 60% of young people have missed school because of anxiety. Demand for mental health services is rising. The waiting lists are too long. So young people and adults are turning to chatbots for emotional support.

But there are very significant risks.

The AI tools do not challenge harmful thoughts or behaviour in the same way as a therapist. A couple in California are suing Open AI over the death of their 16 year old son who tragically took his own life earlier this year. His parents allege that ChatGPT validated his most harmful and self destructive thoughts and became his closest confidant in the months before his death.

I listened last week to the Flesh and Code podcast (Season 2; from Wondery) telling the story of the Replika AI chatbot; the ways in which people become emotionally dependent on AI; the risks of distorting our humanity and our deepest relationships.

Something very disturbing is happening. Flesh and Code describes the way in which significant numbers of people are forming dependent relationships with AIs which they believe are akin to marriage.

The podcast also tells the story of how a vulnerable teenager is now serving a prison sentence because the chatbot spurred him on to make an attempt on the late Queen’s life.

The Precautionary Principle

One of the most basic ethical principles for the adoption of new technology is the precautionary principle. If something might be unsafe or harmful to the public, it is the responsibility of the developer to test that product to the standards required by wider society and that testing should be required by governments the world over. The greater the risk, the more rigorous the testing.

These are the principles that apply in, for example, aircraft design, the testing of drugs or introducing a new car to the marketplace. No-one would release a new tool of any kind to the public by saying: ‘here’s something interesting to deploy – it might have some harmful effects we haven’t quite ironed out yet, we don’t really know, but go ahead and use it anyway’. But that seems to be exactly what the major technology companies are able to do with complete freedom with new AI products. Can that be right or fair?

Parmy Olson’s book describes the vast wealth of the major tech companies and yet the paltry sums which are invested in independent online safety. If the technology was causing physical harm which could be measured (such as medical side effects; or car crashes with deaths and injuries) the products would be pulled from the market until they could be improved.

A very real cost

But what if the cost cannot be measured so easily but is still real? What if the cost is the mental health of the most vulnerable? Or the mental health and resilience of a whole generation of young people? What if the cost is the further degradation and abuse of women and girls online?

Should there not be the same outcry, the same call for regulation, the same appeal to self regulation and to greater government oversight?

As recently as last week, President Trump publicly criticised the UK for the provisions of the Online Safety Act – one of the strongest defences in the world for vulnerable children and young people (and still not strong enough in my own view).

AI can bring and is bringing major benefits. But we need to wake up as a society to the risks as well as the benefits of technology, in the present as well as in the future.

The UK needs a wider public debate and more communities of resistance – and the churches and faith communities have a key part to play. We need a new AI bill which will regulate the deployment of new technology and insist on robust safety testing.

We are sleepwalking into madness and the erosion of public confidence. It is time to act.